Elaine Storkey unpacks the biblical story of Esther’s to reveal her courage in risking her own security to preserve the lives of others

Study passage: Esther

If we were living in the Persian empire around 480 years before Jesus, we would have had to watch our step carefully as women. As in many cultures, we would have been powerless and marginalised and any freedoms would have been limited. It wouldn’t have made a huge difference either whether we were immigrants in the culture or part of the dominant ethnic majority; we still would have had no rights or authority of our own. As women we could not make our own decisions. We would not even have had much choice about whether we got married or not, or to whom. And whether we were wives, daughters or servants, our role would have been to do as we were told.

Pawns in the king’s game

Both Esther and Vashti were married to the most powerful man in Persia, King Xerxes. His wealth was enormous: the book of Esther gives us descriptions of his mosaic pavements of mother-of pearl, other costly stones and his couches of gold. Even his gardens dripped with opulence as hangings of purple and fine white and blue linen were festooned on marble pillars by silver rings (see Esther 1).

The story opens with a six-month public display of the king’s magnificence, ending with a week-long banquet. The guests (all male of course) had as much rich food and wine in gold goblets as they could consume, while the king’s wife, Queen Vashti, held her own banquet for the women (Esther 1:9). When Xerxes had displayed everything he owned to great effect, he had one final exhibit he wanted to show off – the stunning beauty of his wife.

So, he called her to walk before his guests. However, Vashti decided that she didn’t want to be displayed and ignored him, producing something of an anti-climax to the party! Her furious husband gathered his advisors and between them they agreed that this would set a bad precedence for all wives in the realm, unless it was dealt with.

So the decree was that Vashti should be banned from the king’s presence and a declaration made throughout his kingdom that “every man should be ruler over his own household” (1:22). The king’s harem was extended with more beautiful young virgins, and Xerxes set about finding himself a new, compliant wife.

As in many cultures, we [women] would have been powerless and marginalised and any freedoms would have been limited

Esther was part of the Jewish diaspora, living in a province of Persia and brought up by her cousin Mordecai, after her parents died. As a woman of outstanding beauty, she was selected to enter Xerxes’ harem and quickly won favour with Hegai, the king’s eunuch in charge of the harem (2:9). She was given the best quarters and seven attendants, while cousin Mordecai checked from a distance that she remained safe.

Natural beauty was clearly not enough for King Xerxes, however. Before the women were sent to have sex with him, they had to undergo a year of beauty treatments of oil, myrrh, perfume and cosmetics (2:12)! Nevertheless, when her time finally arrived, Esther overwhelmed him with her beauty and spirit and he chose her as his new queen. A national holiday was proclaimed, she was crowned at yet another banquet and liberal gifts were distributed by the king (2:17-18).

The courage to put herself on the line

All this time, Esther had kept quiet about the fact that she was Jewish. Mordecai had also kept a careful eye on things at the palace gate. When he overheard a plot to overthrow King Xerxes he passed the information to his cousin, who told her husband, and the insurrection was foiled (2:19-23). The real crunch came, however, when Mordecai’s Jewish faith led him to refuse to kneel to Haman, the king’s nobleman. Haman wanted his power to be seen everywhere, so this refusal unleashed a torrent of fury from the ambitious Persian. From then on, a plot to eradicate not only Mordecai, but the whole of the Jewish diaspora, was put in motion and looked likely to succeed.

Only Esther had any potential to save them, but she first had to take the risk of approaching the king without being summoned by him. This cardinal rule ensured that the king alone decided who could enter his presence. Since he had not summoned her for 30 days (which may have meant she was out of favour), she realised the danger this would put her in (4:10-11). But the bigger danger was that unless she could persuade the king to stop the cull, all her people would die. After a period of fasting and waiting, she made her move.

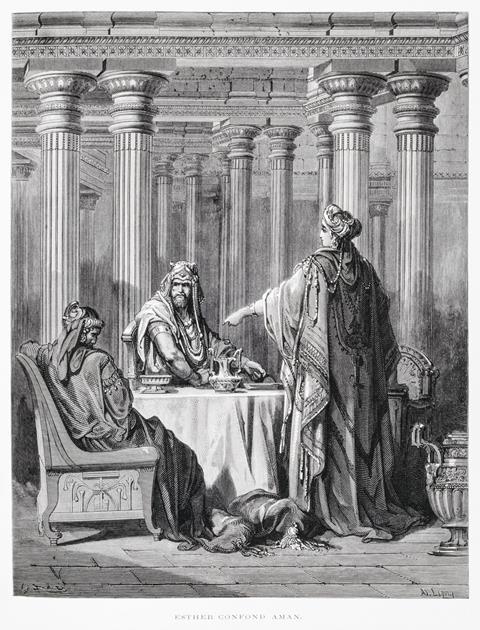

Xerxes did allow her to enter his presence, discovered Haman’s purpose to kill Mordecai (who had previously saved the king’s life) and to eradicate the whole Jewish population, including Esther. The end result was that Haman himself was executed, Mordecai became prime minister and the Jews were given permission to wipe out their enemies. A whole chapter then provides a gruesome account of bloodthirsty vengeance on all those who would harm the Jewish population.

The only note of restraint is that the Jewish people refused to plunder their enemies. Instead, they inaugurated the festival of Purim, to commemorate their deliverance from annihilation in Persia and to give thanks to God. To this very day, the Jews celebrate Purim each year, beginning the festival with a ritual fast and a reading of the book of Esther.

What can we learn from the book of Esther today?

The Jewish people themselves raise many questions about the story and its place in their scriptures. Rabbinic commentators have expressed concern for Esther’s failure to live as a Jew: she lived in the Persian court in a harem, did not follow Jewish dietary laws, had sex and then married a Gentile. Even more troubling is that God is not mentioned in the text, prayer is not stressed and there is nothing supernatural in what occurs in the account of the Jews’ deliverance.

Yet the event is still commemorated along with key miraculous events in Jewish history, such as the crossing of the Red Sea. For Jewish readers, then, the deeper point of the story is that God is always present, even when hidden from view, and that the power of God is made available to his people through fasting and lament.

In our contemporary world, we have different concerns. For example, the end of the story is horrendous. Mass killings is not a great way to achieve stability and a peaceful future. Of course, these were violent times and the Jewish people had to fight for their survival. Yet it seems so contrary to the way we are asked to deal with our enemies in the New Testament, where reconciliation and forgiveness are uppermost in Jesus’ teaching.

The story stands as a grim reminder of who holds the power in patriarchal societies

The other issue that leaps out at us is the way women were seen, as reflected in both the wives of Xerxes. The story stands as a grim reminder of who holds the power in patriarchal societies, echoed elsewhere in the Bible and in the stories in my book, Women in a Patriarchal World (SPCK). Yet the fact that the story of Vashti and Esther appears in the Bible is significant. We might well commend Queen Vashti for not wanting to be paraded as her husband’s property, but we can commend Esther even more – for her willingness to put her own life at risk to save her people.

It was Esther, not her cousin Mordecai or any other God-fearing Jew, who prevented the annihilation of the Jewish diaspora in ancient Persia. The pliant and obedient Esther became a woman of action risking her own security and future in order to preserve the safety of others. Her resolve: “I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. And if I perish, I perish” (4:16) rings down the centuries as a gesture of defiance and courage for faithful, inspirational women.

Esther is a forerunner of women of faith through the centuries, many of whose names we shall never know. But hundreds of others we do know and celebrate, especially those women of the last few centuries whose courage took them to far-flung places in Christian mission, or enabled them to stand against tyrannies and political evil. Here are just a few: Susanna Wesley (1669–1742), Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), Harriet Tubman (1822–1913), Fanny Crosby (1829-1915), Mary Slessor (1848–1915), Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati (1858–1922), Evangeline Booth (1865–1950), Amy Carmichael (1867–1951), Corrie ten Boom, (1892–1983), Gladys Aylward (1902–1970), Florence Li Tim Oi (1907–1992), Lyn Lusi (1949–2012) and Leah Sharibus (2003–).

So let us all ask God to give us the courage to stand firm against whatever wrong we encounter and be willing to take risks for the safety of others.

No comments yet