This month Amy Boucher Pye is reading…

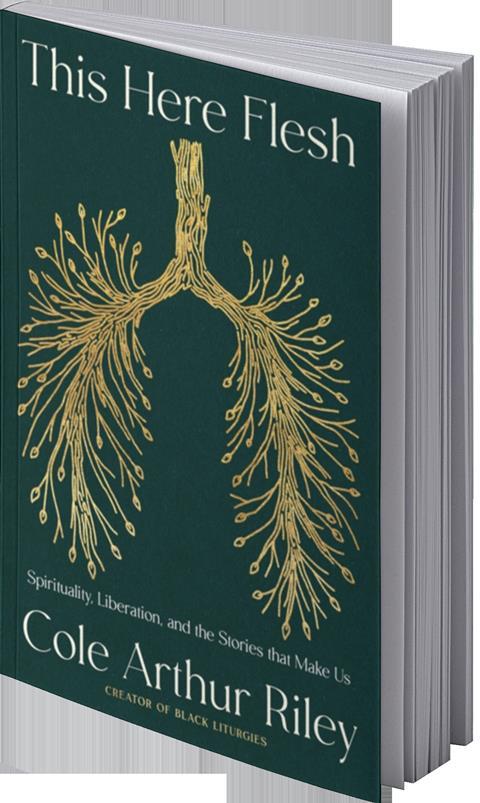

This Here Flesh

Cole Arthur Riley (Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 978-1529372793)

I heard a lot of buzz about This Here Flesh and, having read it, I can understand why. Cole Arthur Riley has written a searching, thought-provoking book of what she calls “contemplative storytelling”. She hits the cultural pulse of what many people are grappling with these days, contributing to the discussion with poetic prose. I didn’t always agree with her, but that’s part of the beauty of her invitation to delve into these topics. She’s not demanding agreement, but welcoming us to think, ponder and add our own unique voices.

Cole writes from a Black American woman’s perspective and, although at times I felt she was reacting to white evangelicalism in the States, overall I found her viewpoints compelling. I highlighted many lines, and wish I could discuss this work in a book-club setting, for I’d love to hear what others think. Her book is best read in community – which I believe is what she’d advocate (considering she dedicates a chapter to community: ‘belonging’).

I read her book at the same time as reading I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (Random House, 1969), which I didn’t plan but I found the two echoed some similar themes from different time periods. Both authors come from mixed-race backgrounds and both had rape in the family experience – the trauma of Black American women too often silenced. Both had grandmothers as the major maternal figure (with Cole’s mother strikingly absent from her book). Both authors stretched me and made me consider my own assumptions as a white woman born into privilege.

I most enjoyed Cole’s chapters on dignity, place, wonder, belonging, rest and joy, but I needed to read those on fear, lament, rage, justice and liberation. To get a taste for her wonderful crafting of words and ideas, ponder this sentence (about the fall of humanity and how God clothed Adam and Eve): “On the day the world began to die, God became a seamstress…no one ever told me the story of a God who kneels and makes clothes out of animal skin” (page 13). I love her visual language.

Or consider what she shares about wonder, about how we need to exercise this practice in order not to fall foul to disillusionment: “Wonder, then, is a force of liberation. It makes sense of what our souls inherently know we were meant for…My faith is held together by wonder – by every defiant commitment to presence and paying attention” (pages 40–41).

In recommending this book, I need to mention that the author uses language that many find offensive (and I didn’t find its inclusion necessary) and uses ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘they’ pronouns for God. Do read it with an open and engaged mind.