Northern Irish writer Rachel Hanna shares her thoughts on the award-winning film Belfast, that sees families struggle with the difficult choice between staying in a war-torn city or fleeing to unfamiliar and potentially hostile lands for safety.

I often say there’s nowhere like Belfast on a sunny day. There’s just something about the way redbrick houses and blue skies meet. Throw in the yellow glow of Samson and Goliath, the famous shipbuilding cranes that dominate the skyline, and it just feels like home.

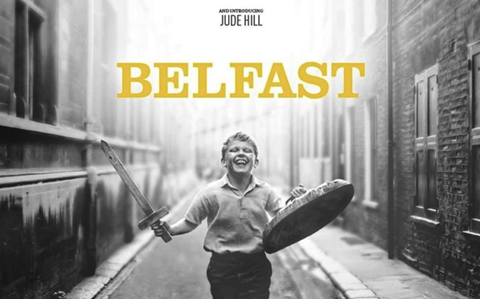

Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast is a tribute to the beauty and brokenness of the city he left as a boy. The movie opens with colourful shots of present-day Belfast, then shifts to a glossy black and white to take us to the scene of the story – it’s summer 1969 and Van Morrison provides the soundtrack to life in a working-class community in North Belfast. Apparently idyllic community life is quickly interrupted by an act of violence, the first evidence of the growing tension between Protestants and Catholics across the country.

We see events through the eyes of Buddy, a young boy who loves going to the movies, and whose main goal in life is to sit next to the girl he loves in school. It doesn’t matter to him that he is a Protestant, and she is a Catholic. He sees all the events in his family’s life like scenes from the westerns he watches on television, sensing threat while not grasping the seriousness of what is going on around him.

Buddy’s family were Protestants, who showed no animosity towards their Catholic neighbours, but labelled Catholicism as a religion of fear.

Aside from the movies, Buddy also loves his family, especially his granda (played by Ciaran Hinds) and granny (Dame Judi Dench). The strength of these family ties and sense of place deeply resonated with me as I watched. Even as the threat to Buddy’s family increases, and tension between his parents grows, Buddy’s mother cannot countenance leaving her home. The thought of leaving her protective web of community and relationships is terrifying because it is a huge part of her identity – all she has ever known. She fears being treated with contempt on arrival in England, for taking English jobs and being indirectly responsible for the deaths of Englishmen serving in the British army in Northern Ireland. Her reflections made me think about our attitudes to refugees and immigrants today – do we welcome or condemn; do we unfairly hold them responsible?

The portrayal of God and the church is damning. Buddy’s family were Protestants, who showed no animosity towards their Catholic neighbours, but labelled Catholicism as a religion of fear. However, Buddy’s local minister is a maniacal hellfire and brimstone preacher, aiming to terrorise his congregation – while collecting their tithes. The point is clear: the use of fear is not exclusive to one religious group! God and religion are removed from the real everyday lives of people, clearly unconcerned with their suffering. Sadly, the stoicism and religiosity imbued in the culture leaves little room for the concept of a loving and welcoming Father God, who has something to say about the suffering and pain Buddy’s family experiences.

Branagh dedicates the movie to those who left, and to those who stayed. I found these to be gracious words of blessing and absolution for anyone faced with such a choice.

As the film ends, and the family make their decision, a heart wrenching line is drawn between those who leave and those who stay behind. In fact, Branagh dedicates the movie to those who left, and to those who stayed. I found these to be gracious words of blessing and absolution for anyone faced with such a choice. Belfast reiterated to me what I already knew about Northern Ireland and its values: family, place and belonging are blessings that can easily become idols. While we may not face the danger Buddy’s family did, might the comfort of the safe and familiar, or a sense of duty and obligation, prevent us from being led to new places and opportunities?

No comments yet