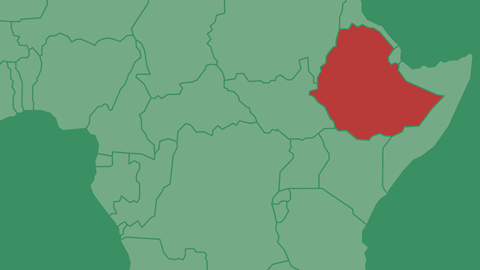

Dr Sheila Akomiah-Conteh explains how Ethiopia escaped Western colonisation and the effect this had on the country’s faith and stability

Ethiopia is no ordinary nation. While almost the entire African continent was carved up by European empires during the late 19th century, Ethiopia stood firm and unconquered. Alongside Liberia, it remains one of only two African nations never formally colonised.

The defining moment came in 1896 at the Battle of Adwa, when Emperor Menelik II’s forces crushed Italy’s invading army. The victory was so decisive that historian Harold Marcus later described it as “the first crushing defeat of a European colonial army by an African force”.1 Adwa not only embarrassed Italy but extinguished any remaining European ambitions to colonise Ethiopia. Across Africa and the diaspora, the triumph reverberated as a thunderous declaration of dignity, resilience and sovereignty. For colonised peoples, it was more than a military victory – it was proof that Africa could and would resist foreign domination.

Yet Ethiopia’s significance runs deeper than battlefield glory. Long before European missionaries set foot on the continent, Ethiopia was already Christian. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, tracing its history back over 1,600 years, preserves one of the world’s oldest and most independent Christian traditions. With echoes of Judaism, a distinctive biblical canon and its fierce independence, the Church dismantles the tired myth that Christianity is a ‘white man’s religion’. Instead, Ethiopia reveals that Africa has always been at the heart of the Christian story.

This article uncovers how Ethiopia defied colonisation through military strategy, diplomatic shrewdness, cultural pride and spiritual conviction. It also traces Ethiopia’s story in the Bible narrative, and explores the extraordinary legacy of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and its role in safeguarding Black identity, religious heritage and faith across the centuries.

Ancient statehood and religious pioneering

“Centuries before the scramble for Africa, Ethiopia was already a great power. The kingdom of Aksum (1st–7th centuries CE) was among the most advanced civilisations of the ancient world. With its own written script (Ge‘ez), monumental stone architecture and a flourishing international trade, Aksum stood alongside Rome, Persia and India as a centre of influence.2

Its might was not just symbolic. Aksum controlled commerce at the crossroads of the Red Sea, linking the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean. Through the bustling port of Adulis, Aksum exported gold, ivory, incense and animal hides while importing silk, wine and fine glassware. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century CE trading manual, notes Aksum as a vibrant hub, connected to Rome, India and Arabia.3

Visitors to northern Ethiopia today can still see the towering stelae – carved stone obelisks that once marked royal tombs. Rising over 20 metres, these monoliths testify to Aksum’s engineering genius and enduring presence. Archaeologists have called them “the largest single pieces of stone ever worked in the ancient world”.⁴

It was within this powerful state that Christianity took deep root. In the fourth century, King Ezana converted to Christianity, making Aksum one of the very first empires to embrace the faith officially. Ethiopia’s Christian identity was therefore not imported centuries later by European missionaries, but woven into its national fabric from antiquity.

Diplomacy and religion

Ethiopia’s survival has always depended as much on diplomacy as on battlefield strength. Throughout history, its rulers have cultivated an identity as an ancient Christian empire descended from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. This Solomonic claim, enshrined in the Kebra Nagast (‘Glory of the Kings’, a 14th-century national epic text, written in Ge‘ez), gave Ethiopian monarchs a biblical legitimacy in the eyes of Europe.

Scholar Steven Kaplan notes that “Ethiopian rulers consistently deployed the symbolism of a Christian empire as a strategy to legitimise their autonomy.”⁵ By presenting themselves as guardians of a biblical lineage, Ethiopian kings could command respect even among the most sceptical Europeans. Unlike other African polities, Ethiopia was treated not as a ‘pagan’ land to be conquered, but as a Christian partner – albeit one fiercely protective of its independence.

This diplomatic identity proved decisive in allowing Ethiopia to hold its ground long before Adwa.

Earlier resistance to religious colonisation

From the medieval period onwards, Ethiopia faced repeated threats to its spiritual and political integrity. Islamic advances across the Horn of Africa from the 13th to 16th centuries placed pressure on the empire, yet the Orthodox Church remained the anchor of unity. Unlike some other nations in Africa, which were taken over by Islamic conquest, Ethiopia has remained a majority Christian country to date.

The greatest challenge came in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Jesuit missionaries attempted to put Ethiopia under Roman Catholic authority. Though they initially gained influence at court, popular uprisings and fierce clerical resistance forced Emperor Fasilides to expel the Jesuits in 1633. In the wake of this triumph, Fasilides founded the new capital at Gondar. Its castle complex, often nicknamed the ‘Camelot of Africa’,⁶ still stands as a symbol of Ethiopia’s determination to chart its own course.

As historian Donald Crummey observed: “the Orthodox Church emerged as the symbol of Ethiopian independence and the vehicle of national identity”.⁷ By resisting religious colonisation, Ethiopia preserved its spiritual authenticity at a time when most of Africa had yet to encounter European expansion.

Ethiopia in the Bible and the Judaic heritage of its Christianity

Ethiopia’s identity is deeply entangled with biblical memory. The land of Cush – often translated as Ethiopia – appears throughout scripture (a territory that, while often identified with Nubia, modern Sudan, occasionally extended into what is now Ethiopia). This early connection finds expression in Genesis 2:13: “The name of the second river is the Gihon; it winds through the entire land of Cush.” Genesis places Cush in the geography of Eden. Moses is described as having a Cushite wife (Numbers 12:1). Prophetic biblical scriptures envision Cush stretching out its hands to God. Psalm 68:31 declares: “Cush will submit herself to God”, a verse long interpreted, especially within Ethiopian tradition, as foreshadowing the nation’s future embrace of Christianity.

Most famously, Acts recounts the baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch, a royal court official serving Queen Candace (Acts 8:26-40). His conversion made Ethiopia one of the first nations woven into the Christian mission. For Ethiopian tradition, this was not symbolic but historical proof that the faith entered their land at its very dawn.

Equally formative was the Kebra Nagast, which narrates how the Queen of Sheba bore a son with King Solomon, Menelik I. Through him, Ethiopia inherited both royal legitimacy and, according to tradition, the Ark of the Covenant itself. While historians treat this as a mythologised political epic, its religious power has been immense. As Edward Ullendorff observed: “The Kebra Nagast is not merely a literary work but the repository of Ethiopian national and religious feelings.”⁸

Ethiopian Christianity is also marked by a striking continuity with Judaism. Its churches preserve customs that vanished elsewhere: strict dietary laws, circumcision on the eighth day, observance of both Saturday and Sunday as holy days, and deep reverence for the Old Testament. As Steven Kaplan put it: “No church anywhere in the world has remained as faithful to the letter and spirit of the Old Testament as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.”⁹

These biblical references to Cush, the Solomonic myth and Jewish observances, give Ethiopian Christianity a depth of heritage unmatched anywhere else in the Christian world.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is utterly unique within global Christianity. Its vast biblical canon includes books long lost elsewhere, such as 1 Enoch and Jubilees, which shape its theology with a sense of cosmic struggle, divine justice and prophetic vision.

Every Ethiopian church houses a tabot, a consecrated replica of the Ark of the Covenant kept hidden from public view except during great festivals. At Timkat (Epiphany), entire towns erupt in colour as priests carry the tabot in procession, accompanied by music, dance and chants that trace back to the sixth century.

The liturgy itself is immersive: drums and sistrums echo against stone walls; incense clouds the sanctuary; the faithful sway and ululate in response to hymns that rise and fall like ancient laments. On Easter in Lalibela, where eleven rock-hewn churches carve directly into the mountain, worshippers gather through the night. As dawn breaks, the chanting builds to a crescendo, drums reverberate and pilgrims raise white-shrouded arms skyward. Few experiences anywhere capture the spiritual intensity of Ethiopian worship.

Theologically, the Church belongs to the Oriental Orthodox family, affirming miaphysitism. This is the belief that Christ’s divinity and humanity are united in one nature. Often misunderstood outside the tradition, this theology expresses Ethiopia’s deep commitment to the mystery of incarnation and its conviction that salvation is the union of the human with the divine.

The Church also shapes everyday life. With nearly 180 days of fasting a year, Ethiopian Christianity demands a discipline and communal rhythm that few other Christian traditions maintain. Its spirituality is not ‘Sunday only’ but a constant shaping of time and appetite, drawing believers into a life-long spirituality of humility and devotion.

A beacon of resistance and inspiration for Black history

Ethiopia’s survival was not inevitable. Repeatedly besieged – by Muslim sultanates in the medieval period, by Portuguese missionaries and by European powers – it endured through a fusion of military defiance, religious unity and cultural pride.

The victory at Adwa in 1896 crystallised this resilience for the world. WEB Du Bois later wrote that Adwa was “the victory of the Negro”, proving that Black nations could not only resist but defeat European empires.

For enslaved and colonised Africans across the diaspora, Ethiopia became a symbol of hope. Marcus Garvey’s movement [Garveyism] also adopted Psalm 68:31 as a rallying cry. In Jamaica, the Rastafarian faith revered Ethiopia and Emperor Haile Selassie as symbols of redemption. African American churches looked to Ethiopia as proof that Christianity had African roots independent of slavery and colonialism.

Thus, Ethiopia’s story became inseparable from the Black freedom struggle worldwide. It was not merely an African kingdom, but a living metaphor of dignity, sovereignty and faith.

Contemporary reflections and ongoing legacy

Today, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church counts tens of millions of adherents. It remains a spiritual and cultural anchor both within Ethiopia and among diaspora communities in North America, Europe and beyond. Its canon, liturgy and traditions are not relics of antiquity but living practices that bridge past and present.

For Black History Month, Ethiopia offers a narrative that is both eye-opening and empowering:

A symbol of resistance By defeating colonial powers, Ethiopia proved African capacity for self-determination.

An ancient Christian nation Ethiopia demonstrates that Christianity has deep, indigenous African roots.

A custodian of heritage Ethiopia preserves ancient practices linking Judaism and Christianity.

An inspiration to the diaspora Ethiopia stands as a symbol of hope for Africans worldwide – a land never conquered, deeply biblical and authentically African.

Ethiopia is both ancient and contemporary: the unconquered empire, the Christian kingdom, the custodian of biblical heritage and the beacon of Black freedom. Its story shows how faith and identity can fortify a people against even the most powerful of external threats.

This Black History Month, Ethiopia invites us to reflect on resilience rooted in spirituality and history. More than a relic of the past, it is a living testimony that Africa was never outside the Christian story. Ethiopia is, indeed, the uncolonised beacon of African Christianity.

References

1. Marcus, Harold (2002) A History of Ethiopia. California: University of California Press.

2. Phillipson, DW (2012) Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000

BC–AD 1300. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

3. Casson, L (1989) The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

4. Kingdom of Aksum. EBSCO.

ebsco.com/research-starters/history/kingdom-aksum#:~:text=The%20most%20important%20testimony%20to,of%20Ethiopia%20in%20the%201930’s

5. Kaplan, Steven (2007) The Ethiopian Orthodox Church. London: Routledge.

6. Gondar: Camelot of Africa, Ethiopia. africanstatearchitecture.co.uk/post/gondar-camelot-of-africa

7. Crummey, Donald (2006) ‘Church and Nation: The Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church (from the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century)’. In Eastern Christianity, edited by Michael Angold, pp457–487. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

8. Ullendorff, Edward (1968) Ethiopia and the Bible, Oxford University Press for the British Academy.

9. Kaplan, Steven (1992) The Beta Israel: Falasha in Ethiopia: From earliest times to the twentieth century. New York: New York University.

No comments yet