‘I’d grown up Christian, been through ordination training, was studying for a doctorate, yet I’d never heard of Marguerite, until a lecturer mentioned the ‘beguine’ mystics in passing. I hunted for stories of these gifted and prayerful women who weren’t cloistered like nuns,’ says Susan Shooter.

Sitting in a café in Kensington, just around the corner from Heythrop College Library, I was overwhelmed by a sense of déjâ vu. I’d been here before. Not in this café, or Kensington, but to the place a new writer was taking me. I say ‘new’ writer. She was new to me, but the author in question died seven centuries ago and I’d lay a bet you’ve never heard her name.

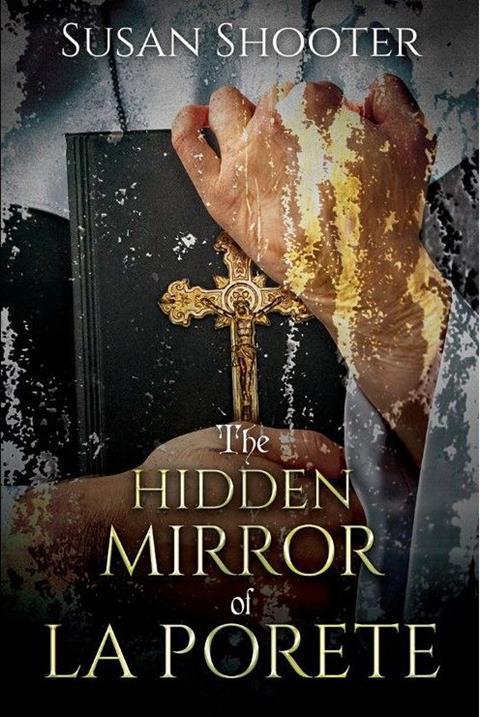

On 1st June 1310, Marguerite Porete was taken to the Place de Grève, Paris, and was burnt alive. Why? She had written a book about Divine Love, claiming to have experienced union with God. Her radical teachings challenged the ‘virtue signalling’ promoted by the medieval church 200 years before Martin Luther tackled the issue.

Proving Virgina Woolf’s point that for most of history, ‘Anonymous was a woman’, Marguerite’s book The Mirror of Simple Souls was separated from her name until the 20th century.

So why did Marguerite’s words stop me in my tracks as I sipped my tea?

READ MORE: Love lessons from mystic powerhouse, Julian of Norwich

I’d finally found a voice that connected with the deep, almost tangible pain of seeking God in dark circumstances.

I’d finally found a voice that connected with the deep, almost tangible pain of seeking God in dark circumstances. Years before, I was suffering from post-natal depression and thought I’d lost my faith—I couldn’t hold onto belief in a ‘loving’ God who could abandon his children to Hell. I was floored. Would I go to Hell for letting go of my God? Then something happened. No flashing lights. No Damascus Road experience. But in the darkness, for a moment, I can’t say for how long, there was a Presence with me.

In that Kensington café, I was reading a description of the soul’s journey through the blind alley I’d once been in.

In that Kensington café, I was reading a description of the soul’s journey through the blind alley I’d once been in. And on the other side, Love was waiting.

I’d grown up Christian, been through ordination training, was studying for a doctorate, yet I’d never heard of Marguerite (or Hadewijch, or Mechthild) until a lecturer mentioned the ‘beguine’ mystics in passing. I hunted for stories of these gifted and prayerful women who weren’t cloistered like nuns. Beguines remained in the world, ran hospitals for the poor, educated themselves, taught girls, and some, at great risk to themselves, wrote theology.

The exclusion of Marguerite’s voice from our spiritual history would be echoed by what I learnt from my research: I interviewed women who had retained their faith despite being victims of abuse. All of them said the interview was the first time they’d been given opportunity to speak about their experiences in relation to their Christian faith. In church, no one wanted to listen.

READ MORE: Nurtured in the hidden places

Very little theology had been written about sexual abuse at this point—this was before 2012 when the Jimmy Saville scandal broke—and spiritual resources to help survivors were sparse. Certainly nothing was written from a survivor’s perspective and I wondered, if someone has walked a difficult path before you, wouldn’t you want them as your guide?

The survivors’ words struck many a chord with Porete’s.

READ MORE: Review of Cabrini: The inspiring journey of a pioneering nun

Imagine this: For a victim of abuse, memories of their will being overwhelmed by someone very powerful can make the idea of submitting to God’s will terrifying. Yet for the women I interviewed, God’s loving presence had transformed them and empowered them. Porete used a comparison to show how this ‘surrendering of will’ is the beginning of a life of love: just as the River Seine loses its name (its identity) when it reaches the sea, it remains part of the ocean, merging with it and acting in it. In other words, when we are united with God, we are filled with God’s goodness and become God’s co-workers. We are not passive bystanders. Likewise, the faithful women I met had not only survived abuse, they’ve thrived, and like our spiritual foremothers, the beguines, they minister to others in need.

The story of a woman who understood spiritual despair and who knew the fullness of God’s Presence cries out to be heard. I felt passionately that Porete needed rescuing from academic libraries and footnotes. Or perhaps that was just me. Anyway, I changed tack. I started writing a novel about Marguerite who has become my mentor in seeking the faith which is nothing other than a surrender to Love.

1 Reader's comment