Elaine Storkey unpacks this story in the book of Ruth, encouraging us to not only be open about our struggles but also to the possibility of God’s restoration

Study passage: The book of Ruth

If you had to choose a name for yourself, what would it be? Would you go for something that describes your personality, a name that sums up your passions or interests, or something that you aspire to be? It’s a difficult task, and thankfully not one we usually have to face, since our names are almost always given to us by other people.

In the book of Ruth, Naomi goes back to her home in Bethlehem, and suggests a name change. Her friends and neighbours are very surprised to see her because she’s been away for more than ten years. When they ask: “Can this be Naomi?” (Ruth 1:19) she tells them not to call her by that name any longer. For Naomi means ‘pleasant’, ‘beautiful’ but her life has not been pleasant or beautiful. Instead, she asks them to call her Mara, which means ‘bitter.’ Naomi is not describing herself as a bitter person but as having endured years of bitter struggle. She is wanting to convey to her old neighbours something of the painful experiences and deep sorrow she has gone through.

The start of Ruth summarises her losses. Her family had once lived in Judah but a famine had afflicted the land, and Naomi’s husband, Elimelek, had decided that they should leave the country and go where food was more plentiful. So he took Naomi and their sons, Mahlon and Kilion, to Moab. In many ways it was a strange choice, not simply because they became ethnic migrants. The Moabites were idol worshippers, whereas Elimelek’s family were faithful Jews who worshipped God. Yet, in spite of all the differences, Moab became their home; the two boys married Moabite women and Elimelek’s family remained there over the next decade.

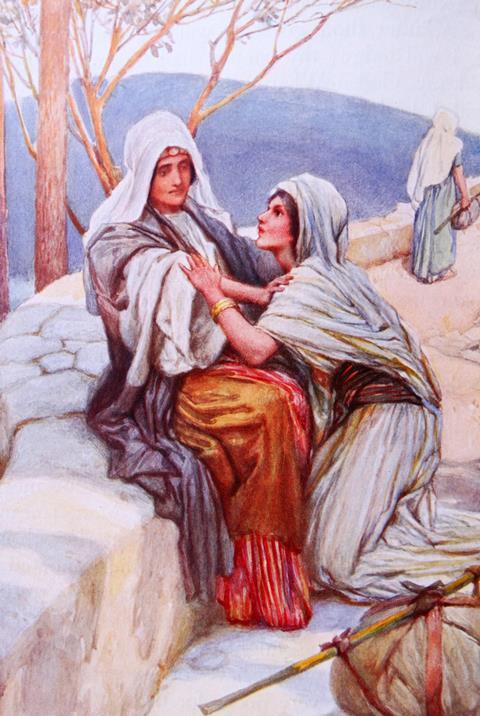

It was not long, however, before they paid the price for the move. Although we are given no details as to the cause, we are told that Elimelek died (Ruth 1:3). Then, to compound the catastrophe, both sons died too. Maybe something in the local conditions in Moab was detrimental to the health and wellbeing of Hebrew men. We don’t know. But Naomi and her two daughters-in-law had to make some difficult decisions about the future. The situation for the younger women seemed straightforward. They could go back to their own families. After all, they were living in their home country. As young Moabite widows they could certainly remarry, and men from their own kinship networks would be available. But there was no future for Naomi in Moab. She was an elderly Jewish woman without a husband, with no means of support. When she heard that the famine in Judah was long-ended she decided to go home, leaving her daughters-in-law behind. Yet they had put down emotional roots with Naomi and didn’t want to part from her. In the end, Orpah stayed in Moab, but Ruth clung to her mother-in-law. Her wonderful cry of love and commitment to Naomi has echoed down the centuries: “Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16).

Back in Bethlehem

After what must have been a long and arduous journey, Naomi and Ruth arrived in Bethlehem. They must have seemed a forlorn couple of widows, quite different from the optimistic family of four who set out for a better life all those years ago. Instead of arriving back with menfolk and children, in Naomi’s own words, they had returned “empty” (v20). Widowhood was not at all a pleasant prospect; even in Judah it could mean poverty and struggle. So Mara seemed to Naomi to be a highly appropriate name, virtually offered to her by God because he had allowed the tragedies to happen.

We don’t know what Ruth felt about arriving in Bethlehem. Naomi at least was going back to her own people, but Ruth was in every sense a foreigner. She was in a land she did not know, with a culture she had experienced only in her relationship with her parents-in-law. Now she would experience it in its fullness. Yet she did not suggest any change of name for herself. Interestingly, she already had been given a Hebrew name, Ruth, which means ‘compassionate friend.’ And her compassionate friendship towards Naomi and her commitment to Naomi’s God reflected the truth of her character found in this name.

Naomi means ’pleasant, ’beautiful’ but her life has not been pleasant or beautiful

Redeemed and restored

There are no more conversations with Naomi’s neighbours until chapter four. The chapters in between reveal the developing relationship between Ruth and Naomi’s relative, Boaz. Ruth first went to glean in Boaz’s fields – a role often reserved for the poor – and came under his protection. He noticed her immediately, hardly surprising since she would not have looked like his Jewish women workers. He made it clear she could be at risk in someone else’s fields and so ensured no one harmed her in his. He also expressed gratitude and admiration for Ruth’s commitment to Naomi, and provided food, encouraging the other workers to leave plenty for her to glean.

Boaz wasn’t acting simply out of philanthropy, however, because such provisions were written into the laws of Moses. The pattern for the people of Israel was to treat foreigners well, and, if someone from their own family became poor or widowed, to ensure that, wherever possible, the closest relative took the responsibility to redeem their loss and restore them appropriately. In Leviticus 25:25, if someone became so poor that they had to sell what they owned to make ends meet, then the closest kinsman had to buy it back for them (Deuteronomy 25:5-6).

Naomi briefed Ruth on how to begin the process of identifying their kinsman-redeemer. She gave Ruth instructions to lie down at the end of Boaz’s bed, thus signifying her willingness to marry him. Boaz was not the closest living relative of Elimelek, however, but the man who was agreed to pass the kinsman-redeemer role down to him. So Boaz bought the land that Naomi needed to sell and married her daughter-in-law. He already loved Ruth and was more than happy to fulfil his responsibilities to them.

We meet Naomi’s neighbours again at the end of the story, after Ruth and Boaz have been blessed with a child. No one is talking about Naomi’s name being Mara at this point. Her life is no longer bitter and empty, but full of rejoicing. Her neighbours praised God for providing Naomi with a kinsman-redeemer and renewing her life with a grandson: “for your daughter-in-law, who loves you and who is better to you than seven sons, has given him birth” (Ruth 4:15). In fact, Ruth’s commitment to her mother-in-law changed history, for her grandson was King David, the biblical author of many psalms and ancestor of an even greater redeemer – Jesus.

All her hopes for the future had gone and it was right for her to name her grief. It is right for us to do so too

What can we learn from Naomi and Ruth’s story today?

Our culture is far from the patriarchy of Israel and Judah, where the provision of a kinsman-redeemer was crucial for the security of widows. Yet, even though widowhood does not automatically mean destitution, it still leaves people with intense grief and loneliness. Making sure that those who are widowed have support and care is one of the responsibilities of the Church. In Orthodox churches, members are urged to make a list of those widowed and keep in close contact with them, offering both practical and emotional help, with special services of commemoration. They also urge their churches to recognise that widowed people have many gifts to offer, and to be sensitive about when to invite them to use those gifts in ministry and mission.

Naomi and Ruth’s story also helps us to realise that any of us might go through painful times, and that it is OK to acknowledge this. Naomi didn’t pretend to her neighbours that everything was fine. After years of distress, all her hopes for the future had gone and it was right for her to name her grief. It is right for us to do so too. Yet just as her struggle with loss was enormous, so was her faith in God. She could not see what might lie ahead, yet she still trusted God to lead her into new hope and restoration. This is also true for many of us. As one door in our lives closes, sometimes bringing heartache, another door eventually opens. And we find, as we go through, that God is beckoning forward, urging us on to a new stage in life. God’s purposes for us do not end with us naming our loss. They continue into the future, often bringing blessings far beyond what we could imagine or even hope for.